01

Yoga: Etymology, Definitions, Objectives and Misconceptions

1.1. Etymology

The term “yoga” is derived from the Sanskrit word "Yuj", related to the "yoke" in its meaning as a uniting element. Thus, yoga is the union of the body, breath, and mind — a state of harmony at all levels of our existence. Yoga means “uniting with the being”.

1.2. Definitions of Yoga

Maharishi Patanjali, in the Yoga Sutras, defines yoga as: “yogah chitta vritti nirodha”, which means “Yoga is the arrest of mental processes”. Thoughts are like waves on the surface of a lake. When the waves cover the surface, nothing else can be seen. Only when the waves subside are you able to see the depth of the lake. Similarly, only when thoughts are softened does a person reach their natural self. As Maharishi Patanjali explains: “tada drashtuh swaroope avasthaanam”, which means “yoga is establishing oneself as the observer (drista)”.

Yoga is the ability to remain centered as Lord Krishna says in the Bhagavad Gita (2.48). “samatwam yoga uchayate”, that is, “Yoga is being equanimous.” For example, the failure to fulfill a desire may lead to sadness, anger, or agitation, while the fulfilment of a desire leads to excitement. Both options take us away from our centre, like a pendulum that flows in the comings and goings of life. Yoga keeps us balanced at all times.

Krishna later elaborates in more detail in the Bhagavad Gita (2.50) "yogah karmasu kaushalam", which means "Yoga is skill in action." Yoga is the skill of living life, managing the mind, and dealing with emotions. Yoga provides skills to actions and the way we communicate because we transmit more through our presence than through our words.

Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha, one of the oldest surviving yoga texts, beautifully describes yoga as “manaḥ praśamanopāyaḥ yoga ityabhidhīyate” – yoga is considered an effective technique for calming the mind.

Furthermore, the purpose of yoga, according to Maharishi Patanjali, is "heyam dukham anagatam" (PYS 2.16), which means "to prevent misery before it occurs" — to “nip it in the bud.”

The origin of yoga dates back to the Vedas.

1.3. Purpose and Objective

The ultimate goal of yoga is to free the individual from the struggles of life.

Yoga, through its systematic and conscious practice of calming the mind, erases the weaknesses of the mind and builds willpower. In that mind, every obstacle is conceived as a challenge and this awakens tremendous energy to combat the situation. Courage becomes part of the personality, firm to the depths. Such a person takes on life's challenges with temperance and turns them into opportunities to fulfill their mission.

The practice of yoga produces certain benefits:

1.4. Common Misconceptions

02

Yoga: Its Origin, History, and Development

2.1. History and Development of Yoga

Yoga is believed to have existed at the beginning of civilization, even before religion and religious doctrines as we know them today began. In the yogic tradition, Shiva is known as the first yogi or Sadashiva and the first guru or Adi Guru.

Legend has it that, several thousand years ago, Sadashiva imparted this profound knowledge to the legendary Saptarishis or the "seven sages." The wise men took this revolutionary science to different parts of the world. Despite the great distances separating ancient cultures and the fact that no means of communication has been discovered, modern scholars have detected similarities between cultures around the world. However, it was in India where the yogic system reached its peak of perfection.

2.1.1. Pre-Vedic Period

In the Indus Valley civilization, the practice of yoga was important. This is confirmed through the depiction of Pashupati in yogic postures on a stone fragment from this period.

2.1.2. Vedic Period

In this period, the four fundamental texts were born: the Rig Veda, the Samaveda, the Yajur Veda, and the Atharva Veda.

2.1.3. Classical Period

The highlights of the classical era are the Yoga Sutras of Maharshi Patanjali. In addition to containing various aspects of yoga, the eight branches of yoga are identified, which lead the sincere seeker towards liberation — Samadhi.

Another very famous text is the Yoga Bhashya, which contains comments on the yoga sutras made by the wise Maharshi Ved Vyasa.

2.1.4. Post-Classical Period

It was during this period that Tantra yoga and Hatha yoga were developed, and the already existing paths of yoga were promoted. Each path had teachers who wrote extensively about it. Many texts were written during this period, and they still exist today.

Jnana yoga was developed through the teachings of the great Acharyatrayas: Adi Shankracharya, Ramanujacharya, and Madhavacharya.

The teachings of Suradasa, Tulasidasa, Purandardasa, and Mirabai made Bhakti yoga famous.

However, the biggest change from the inside out — from the mind to the body — occurred between 800 AD and 1700 AD. Some of the memorable yogis (Hatha yoga Natha Yogis) who popularized Hatha yoga practices during this period were Matsyendaranatha, Gorakshanatha, Chauranginatha, Swatmaram Suri, Gheranda, and Shrinivasa Bhatt.

The Sixfold Path of Shadanga Yoga of Gorakshashatakam, Chaturanga Yoga (The Fourfold Path of Yoga) of Hatha Yoga Pradipika, and Saptanga Yoga (The Seventh Path of Yoga) of Gheranda Samhita laid the foundations of today's Hatha yoga.

2.1.5. Modern Era

Yogacharyas Ramana Maharshi, Ramakrishna Paramhansa, Paramahansa Yogananda, Vivekananda, dominated the modern era and contributed to the development of Raja yoga.This period was when Vedanta, Bhakti yoga, Natha yoga, and Hatha yoga flourished even more.

2.2. Teachings of the Vedas

The ancients believed that there were two different ways of acquiring knowledge.

2.2.1. Para

The knowledge that does not require learning or qualifications, is beyond effort and is bestowed by the benevolence of the Guru, is known as Paravidya (learning related to the self or the supreme truth).

2.2.2. Apara

Aparavidya is that which requires perseverance; that which is enumerated and studied with a teacher. It is divided into Shruti and Smriti.

2.3. Shruti

2.3.1 Vedas

"Veda" is derived from the Sanskrit root "Vid" which means "to know." It is said in the scriptures that the Vedas are endless “anantai vai vedah”. The intelligence that is the basis of all creation, that governs the nature of things, from stars to atoms, is Veda.

The Rishis were the seers of the supreme truth, not just the creators of the hymns of the Vedas. The Vedas are understood to be "Apaurisheya", which means "not of a man" or "without an author". For example, Newton discovered the law of gravity, but the law is eternal and existed even before Newton discovered it.

The oldest Vedic texts of the Vedic religion are these four:

Each Veda consists of four parts:

There are three different interpretations of the Vedic texts: Shankararcharya's Advaita, Madhavacarya's Dwaita, and Ramanujacharya's Vishitadadvaita. These texts analyze Vedic literature and interpret it in their own way. Shankaracharya wrote commentaries on ten Upanishads and these are considered the main ones.

There is no exact date for the composition of the Upanishads; they continued to be composed over a long period, with the main writings being between the 5th and 7th centuries BC.

Ten Main Upanishads:

2.3.1.1. Brhadaranyaka Upanishad by Rishi Yajnavalkya.

It is widely accepted as the most important of all the Upanishads and is the tenth in a canon of 108 Upanishads. Brhadaranyaka means "great desert or forest Upanishad''. It has three kaandas or parts: Madhu Kaanda, Muni Kaanda and Khila Kaanda.

2.3.1.2. Aitareya Upanishad

This Upanishad is part of the Rig Veda and contains 33 verses, divided into three chapters. The first chapter deals with creation, the second chapter deals with the birth and rebirth of the Atman, while the third deals with the nature of the Atman and consciousness.

2.3.1.3. Chandogya Upanishad

This Upanishad is part of the Samaveda and has eight sections, and they are made up mainly of stories and songs.

2.3.1.4. Kena Upanishad

The name of this Upanishad comes from the first word “Kena”, which means “by whom”. The Upanishad consists of a story about a Yaksha, a divine being, who challenges the earth, water, fire, and air, which have become very arrogant, to destroy a blade of dry grass that he holds in his hands. When none of them can do anything to the blade of grass, they realize that its power exists because of the one universal power — the spirit. The theme of this Upanishad is beautifully summarized in the following verses of the first chapter;

“That which cannot be expressed by speech, but by whose power it is uttered, know it as the supreme Brahman. (1.3)

That which cannot be seen, but by whose power the eyes can see, know it as the ultimate: Brahman (1.5)

He whose sound cannot be heard, but by whose power all sounds are heard, know him as the supreme Brahman.” (1.7)

2.3.1.5. Taittiriya Upanishad

The name is supposed to be derived from the name of the Vedic sage Tittri. This Upanishad is highlighted by the theory of Pancha Kosha (the five bodies or layers of the human). It expresses that man reaches his full potential and understands the deepest knowledge through a process of learning what is right and unlearning what is wrong.

The third chapter, Bhrigu Valli, uses the allegory of food to describe the universe, showing how each aspect of the cosmos is highly interdependent.

2.3.1.6. Isavasya o Isha Upanishad

It is one of the shortest Upanishads consisting of 18 verses and is associated with the Yajurveda. The term "isha" literally means "lord, master, ruler" and "vasyam" "covered, hidden, enveloped by". Therefore, isavasya means "enveloped by the Lord" or "hidden in the Lord."

The Isavasya Upanishad also discusses that one of the many roots of pain and suffering is to consider one's self separate from the self of others and assume that one's happiness and suffering are different from the happiness and suffering of another living being. Such grief and suffering cannot exist, this Upanishad suggests, if an individual realizes the oneness in all existence.

The Upanishad also discusses that a person's material and spiritual goals do not necessarily have to be opposite to each other.

2.3.1.7. Katha Upanishad

Also called Kaṭhopaniṣad, this Upanishad revolves around Yama, the God of Death, and a young Brahman called Nachiketa, who seeks answers to the secret of death and birth.

2.3.1.8. Prasna Upanishad

Prasna means question, and this book is part of the Atharva Veda. It addresses six questions and each is a chapter that analyzes the answers. Each chapter ends with the phrase prasnaprativakanam, which means "Thus ends the answer to the question". The last two sections discuss the power of Om and the concept of Moksha.

2.3.1.9. Mundaka Upanishad

This book also belongs to the Atharva Veda. The name is derived from "Muṇḍ" or "shave", which means that anyone who understands the Upanishads is freed from ignorance. This book highlights the importance of knowing the supreme Brahman.

2.3.1.10. Mandukya Upanishad

It is the shortest of all the Upanishads. It describes the four states of consciousness: Jagrat, Svapna, Sushupta, and Turiya. It also links the four parts of Om with the four states of consciousness.

2.3.2 Vedangas

The Vedangas are six auxiliary disciplines that help people to understand the Vedas.

2.3.3 Upvedas

The part of the Vedas about applying the teachings is the Upvedas. Every Veda has an Upveda or a Subveda.

2.3.4 Upanga / Shad Darshana

Although the six Vedangas help in studying the Vedas, we can approach them from many angles. Thus, there are six Darshanas or Upangas: Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Samkhya, Yoga, Purva Mimansa, and Vedanta. These are the six philosophies inherent in the Vedic scriptures.

The term "Shad Darshanas" refers to the six classical schools of Hindu philosophy, which are also known as the "Six Orthodox Schools" or "Six Systems of Indian Philosophy".

These schools are traditional in the sense that they accept the authority of the Vedas and form the basis of orthodox Hindu thought. Each school presents a unique perspective on metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and other aspects of life.

The Shad Darshanas are:

2.3.4.1. Nyaya

Founded by the sage Gautama, Nyaya is a school of logic and epistemology. Its goal is to provide an understanding of obtaining valid knowledge and correct inferences.

2.3.4.2. Vaisheshika

Attributed to Sage Kanada, Vaisheshika focuses on metaphysics and atomism. It presents a detailed classification of different types of substances and their properties.

2.3.4.3. Samkhya

Samkhya is considered the oldest of the orthodox philosophical systems of knowledge. Kapil Muni (Kapila) is traditionally considered to be the founder of the Samkhya school. Its text is called Samkhya Sutras, but the text available today is the Samkhya Karika written by Ishvara Krishna.

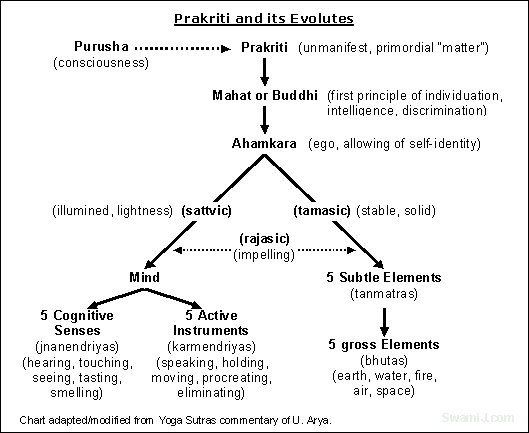

His philosophy analyzes the elements of existence and considers that the universe consists of two eternal realities: Purusha and Prakriti. It is, therefore, a firmly dualistic philosophy.

Samkhya means numbers, so this philosophy reveals the mathematical facets of our universe. What permutation and combination has created this world? What are the 24 elements or Tattwas that are at the centre of creation? Samkhya tells us that Panch Mahabhootas, Panch Tanmatras, Panch Jnanaindriyas, Panch Karmaindriyas, Prakriti, Buddhi, Aham, and Manas, along with the ever-present Trigunas, create all beings and objects that exist in this universe. Samkhya proposes Kaivalya or liberation from the pain of the cycle of birth and death as the ultimate goal of human life.

Samkhya posits that only correct knowledge, which distinguishes our real self (Purusha or consciousness) from our unreal self (Prakriti), can liberate us. Kaivalya is the state where everything else ceases to exist.

2.3.4.4. Yoga

Founded by the sage Patanjali, yoga is a system that seeks to achieve spiritual understanding and tranquillity through control of the mind and senses. It includes ethical and practical guidelines for life. Patanjali Yoga Sutra is composed of:

2.3.4.4.1. Ashtanga Yoga (The Eight Limbs of Yoga)

2.3.4.5. Mimamsa

Also known as Purva Mimamsa, it was developed by Sage Jaimini. It focuses on the study of rituals and the interpretation of Vedic texts, particularly the Brahmanas and Samhitas.

2.3.4.6. Vedanta

Also known as Uttara Mimamsa, it is one of the most prominent schools and is based on the Upanishads. It is often attributed to sage Vyasa. Vedanta explores the nature of reality (Brahman) and self (Atman) and includes several subschools, the most notable being Advaita (non-dualism), Dvaita (dualism), and Vishishtadvaita (qualified non-dualism).

2.4. Smriti

Smriti was further divided into:

2.4.1. Purana

Purana is “pure nava” which means “what is new in town”.

Legend has it that after compiling the Vedas, Maharishi Veda Vyasa was urged by the simple people of the village, who had neither the time nor the intellect to devote themselves to the study of the Vedas but still wanted to learn them to write something more simple and understandable. That is why he composed the 18 Puranas in the form of stories meant to represent and symbolize the wisdom and insight of the Vedas.

Large sections of the Puranas, which are eighteen in number, praise the exploits of Vishnu, Shiva, Brahma, Devi, Gaṇesha, and Skanda or Kartikeya — either in their original forms or in their avatars. The Puranas also describe in detail subjects as diverse as medicine, art, literary appreciation, grammar, ethics, politics, rituals, pilgrimages, religious vows and observances, and the philosophy of Sankhya yoga and Vedanta in a variety of ways.

They also exemplify biographies of wise men, saints, kings, and iconic figures who lived and moved in this world as models of wisdom, power, and moral toughness. Of the eighteen Puranas, six are dedicated to Brahma, six to Vishnu, and six to Shiva. Among the eighteen, pride of place is accorded to Vishnu Purana and the Śrīmad Bhāgavatam from the point of view of vital content, moral wisdom, and religious impressiveness. There are 18 Purāṇas and 18 Up-puranas.

2.4.2. Itihas

Itihas means "so indeed it was." The Ramayana and the Mahabharata are the two stories or itihasas. For a sadhaka (initiated on the path of yoga), it contains what are arguably the two most important texts: the Bhagavad Gita in the Mahabharata and the Yoga Vasishta in the Ramayana.

2.4.3. Agama

Agama is derived from the verbal root "gam" meaning "to go" and the preposition "aa" meaning "towards" and therefore refers to precepts and doctrines "that have come down to us." Even though the ultimate knowledge sees advait or non-duality everywhere, for the mind, worship is the easiest tool to reach the divine. Thus, the agamas prescribe the right methods to adore the divine. The topics of agama texts vary from the four kinds of yoga, temple construction, cosmology, and philosophy to mantras, meditation, and many more.

The five main agamas are:

03

Principles of Yoga (Triguna, Antahkarana-Chatushtaya, Tri-Sharira Panchakosha)

3.1. The Three Bodies

Each individual can be perceived as composed of three bodies:

3.1.1. Sthula Sharira

Sthula sharira or the physical/gross body is composed of the five gross elements (Pancha Mahabhutas). This body is the vehicle through which one gains experience of the world and is subject to birth, growth, change, decay, and finally death.

Pancha Mahabhuta's sons:

3.1.2. Sukshma Sharira

Also known as Linga Sharira, the astral or subtle body, it is the result of our past karmas and is composed of the following parts:

3.1.3. Karana Sharira

Karana Sharira, or the causal body, is the cause of the subtle and gross bodies. It is Prakriti in Sankhya and Atman in Vedanta. Karana Sharira is that which continues after the other bodies leave and contains the seed for a new life in a new body.

3.2. Trigunas

In the context of yoga philosophy, the concept of Trigunas originates in ancient Indian scriptures, particularly Samkhya philosophy, and was later integrated into various yogic traditions, including the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali and the Bhagavad Gita. Trigunas refer to three fundamental qualities or energies that are believed to constitute the essential nature of all phenomena in the universe. These three gunas are:

3.2.1. Sattva (Goodness)

Sattva is associated with purity, balance, and harmony. It represents qualities such as clarity, intelligence, and tranquillity. A person or object dominated by Sattva is characterized by a calm and peaceful demeanour and a clear and concentrated mind. Sattva is considered conducive to spiritual growth and self-realization.

3.2.2. Rajas (Passion)

Rajas is associated with activity, movement, and desire. It represents the dynamic and active aspect of nature. The characteristics of rajas include restlessness, ambition, and desire-seeking. While Rajas can drive action and achievement, excessive attachment to it can lead to imbalance and distraction from spiritual activities.

3.2.3. Tamas (Ignorance)

Tamas is associated with inertia, darkness, and ignorance. It represents qualities such as lethargy, laziness, and confusion. Tamas are considered the lowest and heaviest of the gunas, which causes a lack of consciousness. It is associated with stagnation and resistance to change. However, Tamas is that quality that we need to go to bed and sleep.

On the yogic path, the goal is usually to transcend these gunas and move toward a state of balance and spiritual awakening. Yoga practice, including asanas (physical postures), pranayama (breath control), and meditation, are designed to help people cultivate Sattva, reduce the influence of Rajas and Tamas, and achieve a state of balance and self-realization.

3.3. Pancha Mahabhuta

Pancha Mahabhuta, or the five great elements that are present throughout the universe, arise from five subtle elements called Tanmatras after having gone through the process of division (panchikarna) and combination. The Tanmatras, as they develop in nature, become more and more physical until we can perceive them. These are: sound (Shabda), touch (Sparsha), form (Rupa), taste (Rasa), and smell (Gandha).

3.3.1. Akasha

The subtlest element, Akasha or ether, is the largest element in the universe. The Tanmatra (object of perception) associated with Akasha is Shabda or the vibration perceived by the sense organ, the ear, and associated with the Vishuddha Chakra. The qualities of Akasha are clear, light, subtle, and immeasurable.

3.3.2. Vayu

Vayu literally means “air”. The word "Vayu" is derived from the root "to move." This element is mobile, dry, light, cold, and subtle in nature. The Tanmatra related to this element is Sparsha or the sense of touch transmitted through the sensory organ of the skin. It is associated with the Anahata Chakra.

3.3.3. Agni

The element Agni, Fire, or Tejas is hot, sharp, light, dry, and subtle. The Tanmatra linked with this element is Rupa (form) and the Jnanindriya (sensory organ) responsible for the perception of form is the eyes. Therefore, Agni is identical with light energy. It is associated with the Manipura Chakra.

3.3.4. Jal

The element Apa or Jal or water refers to the liquid forms of matter. The water element exhibits qualities such as freshness, fluidity, and softness. The Tanmatra connected with this element is rasa or taste and the Jnanindriya is the tongue. It is associated with the Svadhisthana Chakra.

3.3.5. Prithvi

The densest element, earth, is the concrete aspect of nature or the solid state of matter, Prithvi or Bhumi, is derived from the root “Bhu”, which means to be. It has qualities such as solid, dense, rough, and very hard. The Tanmatra allied to this element is Gandha or smell and Jnanindriya, the nose. It is associated with the Muladhara Chakra.

3.4. Panchakosha

The Panchakoshas are described in Brahmanda Vali in the Taittiriya Upanishad of the Yajur Veda. This Upanishad provides us with Panchakosha Viveka to help us discriminate between self and non-self (Atma and Anatma).

The word “kosha” means sheath or envelope and “Pancha” means five. In yogic philosophy, Panchakosha represents the five layers of personality of our existence — of our being: moving from the superficial layer of the physical body to the depths of the blissful self.

The Pancha Koshas are:

Sthula Sharira (ver 3.1.1) es Annamaya Kosha, Sukshma Sharira (ver 3.1.2) comprende Pranamaya Kosha (Energía Vital), Manomaya Kosha (Mente) y Vijnanamaya Kosha (Intelecto) y Karana Sharira (ver 3.1.3) es Anandamaya Kosha (Bienaventuranza).

3.4.1. Annamaya Kosha

This is the first layer of our existence. "Anna" means matter, "annam" literally means food. The dense body is born from matter, is sustained by matter, and then returns to merge with matter.

3.4.2. Pranamaya Kosha

The Annamaya Kosha, formed from inert matter, is supported by an envelope of energy. This energetic envelope of our existence is called Pranamaya Kosha. The word “prana” means “life-force energy”.

3.4.3. Manomaya Kosha

Manomaya Kosha is the layer of existence that can simply be called mind, Manas. Manomaya Kosha, according to the Taittiriya Upanishad, is like the “I” or the Atman of the Pranamaya Kosha. Manas is basically the thought layer of our existence; all thoughts rise and sink here. These thoughts have great power to affect our physiology, physical body, moods, and most importantly, our prana. Anxiety and fear, among other factors, cause an increase in respiratory rate. Similarly, love and peace can make breathing longer and deeper.

3.4.4. Vignanamaya Kosha

Vignan means "to know". It is the layer of wisdom that knows, judges, classifies, discriminates and decides. Beginning with the Annamaya Kosha, the five koshas become more subtle and less tangible as we move inward. The Vignanamaya Kosha must be understood in its subtlety.

Vignana is the intellect. This buddhi or intellect helps us classify, evaluate, objectify, quantify thoughts, and quiet them. A study of Vignanamaya Kosha makes you the master of your mind, so an important part of Sadhana yoga is gaining access to this layer.

3.4.5. Ananadamaya Kosha

The Vignanamaya Kosha is driven to judge, classify, conclude and discern from an internal motivation or drive to achieve the state of fulfilment and satisfaction. This impulse is the Anandamaya Kosha, the seat of Satchitananda (subjective experience of the ultimate immutable reality, called Brahman). That level of our existence where we experience contentment is called Anandamaya Kosha. Ananda means bliss. However, Ananda is not an experience of some happy emotions at the level of the mind, but rather it is love, peace, and joy, independent of any mental stimulation. It is simply being in bliss.

04

Introduction to the Main Schools of Yoga (Jnana, Bhakti, Karma, Raja, Hatha, Mantra)

Paths of Yoga

In traditional Indian philosophy, there are several paths or disciplines of yoga, each designed to suit different temperaments and approaches to spiritual growth. These paths are often called “yoga.”

Below are the paths of yoga that have gained prominence in the ancient culture of India.

4.1. Jnana Yoga - The Path of Knowledge

The meaning of the word “Jnana” or “Gyana” in Sanskrit is knowledge. Jnana is concerned with the investigation of the nature of reality. The relationship between the observer, the landscape and the process of seeing is explored. Contemplation and study of being are tools in the search for truth.

Knowing through the senses is information, while experiencing reality gives us knowledge. Therefore, Jnana yoga is not only the study of existence but also a deep experiential understanding of the ultimate reality of life.

In all Indian philosophies, modifications in the mind form veils of ignorance around the self, becoming an obstacle on the path of realization. The path of Jnana yoga seeks to be able to transcend the mind through constant investigation, being aware of the self, and in this way, quieting the fluctuations of the mind.

4.1.1. Steps of Jnana Yoga

Shravana:

Meaning: Shravana translates to “hear” or “listen.

Description: In the context of spiritual practice, Shravana involves actively listening to the teachings of a teacher or the scriptures, particularly those related to the nature of the self (Atman) and ultimate reality (Brahman). The goal is to obtain a clear and correct understanding of these teachings.

Manana:

Meaning: Manana translates to "reflection" or "contemplation."

Description: Once we have heard or studied the teachings, we must reflect deeply on them. This stage focuses on intellectual contemplation, analysis, and clarification of doubts. Practitioners engage in deep reflection to internalize the teachings and resolve any intellectual obstacles or misunderstandings.

Nididhyasana:

Meaning: Nididhyasana is often translated as "meditation" or "deep contemplation."

Description: Nididhyasana is the stage in which the aspirant goes beyond intellectual understanding and engages in deep contemplative meditation. It goes beyond mere thought and involves a sustained focus on the truths revealed in the teachings. The practitioner seeks to directly experience the reality pointed out by the scriptures or the teacher. Nididhyasana leads to a direct and experiential realization of the self (Atman) and its oneness with the ultimate reality (Brahman).

Master Ramana Maharshi guided us by explaining that with Shravana, knowledge arises; with Manana, knowledge is not allowed to disappear; and with Nididhyasana, one is the owner of knowledge.

The process of Shravana, Manana, and Nididhyasana is not necessarily linear; it can be iterative, with individuals moving back and forth between stages as their understanding deepens. The goal is to go beyond intellectual knowledge toward a direct, experiential realization of the truth of one's own nature and ultimate reality.

4.1.2. Four Pillars of Jnana

In order to understand reality, master Adi Shankaracharya established requirements described in his Tattvabodha commentary. These prerequisites are called Sadhana Chatushtaya — the four main tools for self-realization.

The four pillars of Jnana (knowledge), as presented in Tattvabodha, are:

4.1.2.1. Viveka (Discrimination)

Description: Viveka refers to the ability to discriminate between the eternal and the non-eternal, the real, and the unreal. It involves cultivating discernment to distinguish between the permanent and unchanging aspect of reality (Brahman) and the transitory and changing aspects of the material world (Jagat). Discrimination is crucial to understanding the impermanence of the phenomenal world and recognizing the underlying and immutable reality.

4.1.2.2. Vairagya (Dispassion)

Description: Vairagya is the cultivation of dispassion or detachment from worldly desires and attachments. It involves a sincere renunciation of the pursuit of material pleasures and the recognition that true fulfilment comes from transcending worldly pursuits. Dispassion is essential to turning attention inwards and directing energy towards spiritual realization.

4.1.2.3. Shatsampatti (Six treasures)

Description: Shatsampatti refers to a set of six virtues that prepare the mind for self-inquiry and contemplation. These virtues are:

4.1.2.4. Mumukshutva (Desire for Liberation)

Description: Mumukshutva is the intense and sincere desire for liberation (moksha) from the cycle of birth and death (Samsara). It is the yearning for self-realization and the recognition that realization lies in understanding one's true nature as Brahman. This strong desire drives the seeker towards spiritual practices and the search for self-knowledge.

These four stages are considered essential for the aspirant on the path of Advaita Vedanta to progress towards the ultimate goal of self-realization.

4.2. Bhakti Yoga — The Path of Devotion

In the word “bhakt”i there are “bha”, “ka”, “ta”, and “i” (ee). “Bha” means fullness and nourishment, "Ka" means knowledge, "Ta" means salvation, and "I" (ee) means shakti or energy.

When all your intense feelings flow in one direction, it is called Bhakti. Your unconditional love is Bhakti.

God's love is unconditional. Nature loves us all equally. Recognizing this love and reflecting it back to God is devotion. The blossoming of this devotion towards God and towards all the phenomena of nature is the sweetest experience one can have. Due to the above, it is accepted that Bhakti yoga is the sweetest path of yoga.

In devotion, a yogi sees divinity everywhere and in everything and recognizes love as nature itself, not just an emotion. A Bhakti yogi is able to transcend worldly sorrows and pains and experience total freedom through surrender. Surrender to the divine is the simplest way to free oneself from bondage. That devotion and surrender is kindled by the grace of a teacher or guru, by being in the company of other devotees, and by reading and listening to the inspiring stories of Bhakti.

4.2.1. Nava Vidha Bhakti

The nine ways of attaining Bhakti (Nava Vidha Bhakti) were described in Srimad Bhagavatham (7.5.23), these are:

4.2.2. Pancha Vidha Bhava

In the Haridasa Sahitya, the five feelings of Bhakti are explained as follows:

4.2.3. Types of Bhakta

In Chapter 7 Shloka 16 of Bhagvad Gita, the Lord tells us that there are four types of Bhatktas (devotees), namely:

4.2.4. Qualities of Bhakta the devotee

Some of the qualities of a true devotee are mentioned in the verses of Chapter 12 of the Bhagavad Gita (12.13–19) and are summarized below.

advesta sarva’bhutanam maitrah karuna eva cha

Nirmamo Nirahankarah Sama - Dukha – Sukha Ksami (12.13)

Do not harbor hostility towards anyone – advesta. Kindness – maitri. Compassionate – karuna. Free from attachment – nirmamo. Free from selfishness – nirahankara. Balanced in pleasure and pain - sama dukha sukhah. Forgive - ksami.

santustah satatam yogi yatatma drdha - nischayah

may arpita - mano - buddhir yo mad- bhaktah sa mi priyah (12.14)

Contents - santustah satatam. Yogi: one who unites himself - yogi yatatma. Have firm convictions - drdha nischayah. Surrender the mind and intellect to God - arpita mano buddhir.

Yasmannodvijate loko lokan nodvijate cha yah

hardamarsa - bhayodvegair mukto yah sa ch mi priyah (12.15

Someone who does not shake up the world around him – yasmannodvijate. He who is not agitated by the world - loko lokan nodvijate. Absence of excitement, envy, fear and anxiety – hardamarsa - bhayodvegair.

anapeksha shuchir daksha dasino gata - vyathah

sarvarambha - parityagi yo mad- bhaktah sa mi priyah (12.16)

Without desire – anapeksha. Purity – shuchir. Competition in action – daksha. Freedom from anxiety – gata vyathah. Renunciation of the fruits of action – sarvarambha – parityagi.

yona hrishyati na dweshti na shochati na kaanshati

शुभाशुभापरित्याआगी भक्तिमान यह सा मि प्रिया (12.17)

Absence of joy, fear, hatred and desire - hrishyati na dweshti na shochati na kaangkshati. Renounce good and evil - shubhaashubhaparityaagee.

samah shatru cha mitre cha tatha maanapaamanayoh

shitoshna-sukha-dukheshu samah sang-vivarjitah (12.18)

Someone who does not shake up the world around him – yasmannodvijate. He who is not agitated by the world - loko lokan nodvijate. Absence of excitement, envy, fear and anxiety – hardamarsa - bhayodvegair.

tulya ninda stutir mauni santushto yena keachit

aniketah sthiramatir bhaktiman mi priyo narah (12.19)

Equality of spirit in praise and blame - tulya ninda stutir. Quiet – mauni. Content with whatever is involved - santushto yena kenachit. Absence of attachment to a home – aniketah. Firmness in decision – sthiramatir. Devotion to God - bhaktimaan.

4.3. Karma Yoga — The Path of Selfless Service

Karma yoga is the path of selfless service. Give your best without getting attached to the result. When an action is performed selflessly, with total concentration and attention, it brings fulfilment and freedom. Acting without becoming attached to the fruits of one's actions can lead us to union with the self, which is the goal of yoga.

Karma yoga is the selfless giving of oneself through work and arises from love that finds satisfaction in pure surrender without the thought of personal gain or recognition.

4.3.1. Types of actions

There are two types of actions:

Karma yoga is closely linked with Bhakti yoga because without love and devotion it would not be possible to serve selflessly.

4.3.2. The Doctrine of Karma

The word "Karma" simply means action. The action here includes both the mental and the physical. It also includes the act in the external world and its experience or impression in the internal world. The Universal Law of Cause and Effect is synonymous with the Doctrine of Karma (Karma Siddhanta), which describes the consequence of an action where each and every karma engenders a result called Karma Phala and leaves a deep impression on the mind called Samskara.

In absolute accordance with the law of consequences, everything we do, say, and think will come back to us in due time. Just as the fate of an arrow shot from your bow is fixed and predictable, our fate is largely decided by our own karmas.

The action has three forms: one is the latent action, which is going to become action, the second is the action itself, and the third is the impression of the action.

The desire to act in itself is karma; it means seed of an action. The seed of an action is latent karma. Action, as we see, is a seed that has sprouted, turning into a tree. And for the tree to become another seed again is the impression of an action. The impression of one action gives rise to more action. So, karma simply means the strongest impression on the mind — an action that has prompted an impression that is going to be made on the mind in the future. There is dynamism practically everywhere. Every particle of this creation is full of dynamism. And that is why this universe is full of karma.

So, when we say we want to get rid of karma, it simply means we want to get rid of an impression. There are certain impressions we would like to have, others we don't. That's what good karma and bad karma are. Negative impressions are those that cause us pain and suffering. Positive impressions are those that give you happiness and joy in life.

But you also have to get rid of the attachment to a positive impression. Because that also limits you. Nirvana is not only getting rid of negative impressions but also freeing yourself from positive ones. When we become attached to positive emotions or impressions, we limit our existence. When you think you are too good, you always find someone who is not so good or is bad.

There is an example that has been given for thousands of years, that of alum. When you want to purify water, you put a little alum in it. Alum first cleans all impurities and then dissolves. It doesn't stay in it, it just evaporates. Similarly, positive impressions or karmas are essential to get rid of negative karma but without becoming attached to them.

So, karma is the latent impression in consciousness that drives you toward an action. And the present actions; in turn, they create impressions in the mind, in the consciousness, that drive you towards yet another action. Therefore, the impression of an action and its impact are collectively called karma.

The skill is to live in karma but not be affected by it. This is yoga. In Bhagavad Gita, Lord Krishna says very beautifully, “He who sees action in inaction and inaction in action is the most intelligent man.”

4.3.3. Types of Karma

Thus, the Sanchita, the karma accumulated in the past, can be undone. Agami Karma that has not yet borne fruit, which could happen, can be undone. But Prarabdha, which is already here, which exists, which has begun to bear fruit, has to be experienced.

In Bhagavad Gita, Lord Krishna says, "gahana karmano gatihi", which means “unfathomable are the ways of Karma”. You can never point to a particular Karma and say that is the cause of this. You don't know which one will sprout and when. In a field, if you have thrown peanut seeds, sunflower seeds, and mango seeds, they will all sprout at different times.

And the last words of Lord Krishna are not to worry about it. Just do your duty. Do what you have to do, act, and don't worry about the result of the action. Just relax.

4.3.4. Sthita Prajna — Lakshana

In Chapter 2, Verse 54 of the Bhagavad Gita, Lord Krishna describes the characteristics of a "stitha-pragna" or a person of constant wisdom.

In summary, the qualities of Sthita Prajna are:

4.4. Raja Yoga - The Royal Path

Raja yoga, often referred to as the "Royal Path", is one of the classical paths of yoga described in ancient Indian philosophy. It is primarily associated with the teachings of Patanjali, as presented in the Yoga Sutras. Raja yoga is a comprehensive system that includes ethical, physical, and mental practices aimed at achieving spiritual realization and self-mastery. The term "Raja" means "royal" and signifies the highest form of yoga.

4.4.1. Ashtanga Yoga: The Eight Branches of Raja Yoga

4.4.1.1. Yama (Ethical principles)

4.4.1.2. Niyama (observations)

4.4.1.3. Asanas (Physical Postures)

The practice of stable and comfortable physical postures to prepare the body for meditation and spiritual practice.

4.4.1.4. Pranayama (breath control)

Techniques to control and regulate breathing, enhancing vitality and calming the mind.

4.4.1.5. Pratyahara (Withdrawal of the Senses)

Redirect attention inward, withdrawing the senses from external stimuli.

4.4.1.6. Dharan (Concentration)

Focus the mind on a single point or object to develop concentration.

4.4.1.7. Dhyana (Meditation)

Continuous and uninterrupted meditation, which leads to a deep state of absorption.

4.4.1.8. Samadhi (Contemplative Absorption)

The ultimate goal, where the meditator experiences unity with the object of meditation, leading to self-realization and spiritual liberation.

The three inner observances, or the last three limbs of the yoga philosophy, have been described as “trayam ekatra samyama”. It translates as “the simultaneous application of these three (dharana, dhyana. and samadhi) at a single point, is mastery.” And that is called samyama.

4.4.2. Key Concepts in Raja Yoga

4.5. Mantra Yoga

Mantra yoga is the yoga of sound. The word “mantra” is derived from the roots "man", which refers to the mind and "tra" refers to protect. Therefore, the mantra represents that which protects the mind. Mantra is a thought or intention expressed as sound. A mantra is a sacred expression or sound charged with psychospiritual power. The power or potency of the mantra is what exploits and achieves mantra yoga. Yogis use mantras to reach deep states of meditation and invoke specific states of consciousness. The most recognized and important mantra is Om.

4.6. Hatha Yoga

Hatha yoga has its origin in Tantra. It is a form of yoga with a more physical orientation. There are various texts on Hatha yoga like Hatha Yoga Pradipika de Swatmarama, Gheranda Samhita de Sage Gheranda, Goraksha Samhita de Gorakshanath, Shiva Samhita, Yoga Ratnavali, and Yoga Taravali.

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika says:

"Ha" means the Sun and "Tha" means the Moon. The right nostril or Pingala Nadi is dominated by the Sun and the left by the Moon or Ida Nadi. So, the balance between Ida and Pingala is Hatha yoga. In other words, Hatha yoga helps to achieve a balance between both Nadis.

The Ida, Pingala, and Sushumna Nadis begin at the Mooladhara Chakra at the base of the spine. From there, the Sushumna flows directly upwards in the centre, while the Ida passes to its left and the Pingala to its right. In Hatha yoga, Pingala Nadi represents the positive force, Ida represents the negative force, and Sushumna represents the neutral force.

In the Svadhisthana Chakra, the three Nadis come together again and the Ida and the Pingala intersect. The Ida passes to the right, the Pingala to the left, and the Sushumna continues to flow directly upwards in the central channel. The three Nadis meet again in the Manipura Chakra, and so on. Finally, all three are found in the Ajna Chakra, the region of the Pituitary Gland, the Pingala on the right and the Ida in the left nostril. When the three Nadis unite in the Ajna Chakra, the ultimate goal of Hatha yoga is achieved.

Svatmarama enumerates Asanas, Pranayamas and Mudras for the realization of inner Brahman. The text explains that when the mind gets tired of everything that the senses and intellect can acquire and learns to let go of everything, then there is no duality left. All that remains is the atma (soul), which then shines in its own essence unhindered.

The mind is subject to patterns and habits. When subjugated to these, the mind is never still. The first step in freeing your mind from these patterns is to learn to sit comfortably in various postures and gradually focus on restricting your breathing patterns. Once the breath has calmed down and the prana flows into sushumna, all the senses will become still. Internal hearing of subtle sounds is an indication that the mind has calmed down. When all association is cut, even with sounds, the mind is finally freed from its layers of bondage.

The text emphasizes the importance of a suitable Guru not only to learn the asanas but also to use them to their full potential. The grace of the Guru can grant what the reading of countless texts cannot: the experience of yoga, the union that every yoga practitioner dreams of.

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika, written by Swatmarama in the 15th century, outlines the lineage of Hatha yoga. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika reveres this lineage, starting with Sadashiva and passing through Matsyendranath and Gorakshanath before reaching Swatmarama. This lineage emphasizes the transmission of Hatha yoga teachings from teacher to disciple, preserving the tradition through successive generations.

The four angas (Chaturanga) or parts of the practice mentioned in Hatha Yoga Pradipika are:

Gheranda Samhita is one of the three classical texts of Hatha yoga, the other two being the Hatha Yoga Pradipika and the Shiv Samhita. It is a text from the late 17th century and is considered the most universal of the three classic texts on Hatha yoga.

Rishi Gheranda enunciates “Saptanga Yoga” or “Seven Limbs” of yoga. The seven members are:

Hatha yoga is often considered a preparatory practice that purifies the body and mind, making it more conducive to higher forms of yoga such as Raja yoga. Raja yoga focuses on mental and spiritual practices such as meditation and self-realization, which are based on the foundations laid by Hatha yoga. Therefore, Hatha yoga is commonly known as the gateway to Raja yoga.